How much do regularised vortex particles look like singular particles?

Singular vortex particles are neat. By lumping vorticity at a point in space, computing induced velocities and vortex stretching terms is relatively easy. But since a vortex can’t just stop at a point in space, these particles don’t represent a vorticity well.

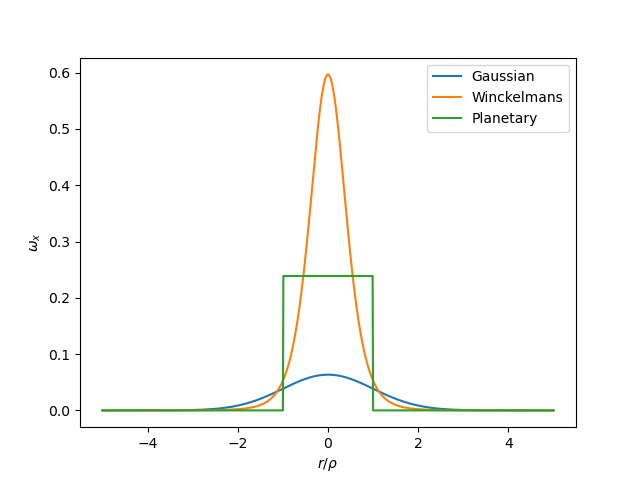

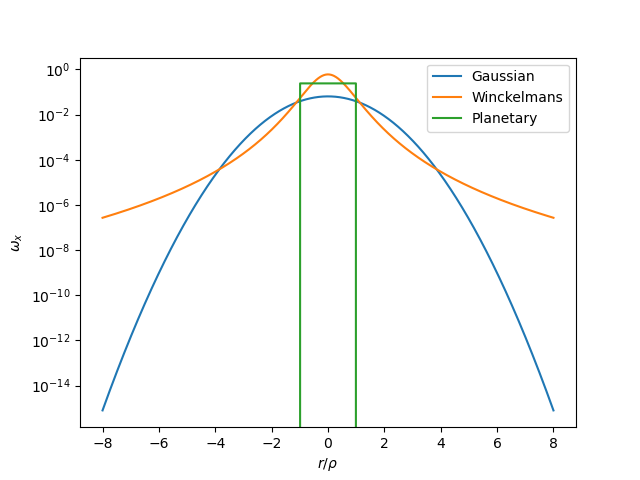

To overcome this, regularised vortex particles can be used. Instead of having the vorticity contained at a singular point (creating an infinite vorticity density), the vorticity is spread out within a small, usually radially symettric volume. Multiple regularisations exist, the most commonly used being the Gaussian regularisation. For a vortex particle in 3D, the vorticity density with respect normalised radius from the centre of the particle is shown below for a few different regularisations:

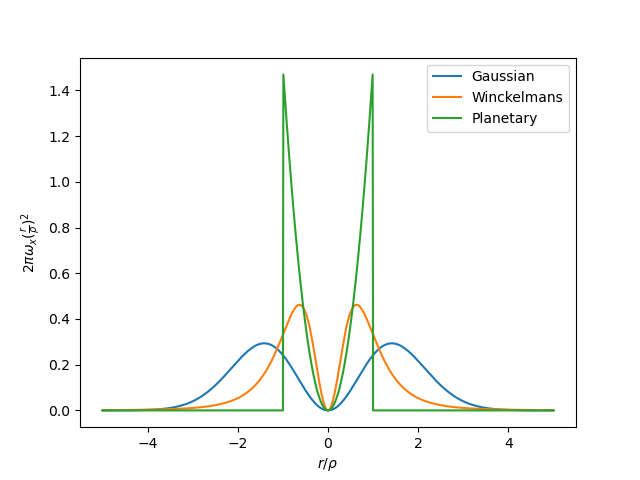

A singular vortex particle would have infinite vorticty at \(r/\rho=0\). Its noticeable that different regularisations seem to have very different peak vorticities. This is because the particle is in 3D, but we’re plotting as we go along the axis. If we instead weight vorticity as \(2 \pi \omega_x (r/\rho)^2\) we obtain:

The integrals of these are curves with respect to \(r/\rho\) are 1.

But to get to the question: how similar are singular and regularised particles? Starting off with vorticity distribution, how far away can we get from the centre of a regularised vortex particle before we can assume vorticity is zero?

A vortex particle using either the Winckelmans or Gaussian regularisation technically spreads vorticity over the entire domain. For practical purposes this vorticity can be ignored after a small radius. An error of order \(10^-5\) is going to be small in comparison to the errors introduced by discretisation. This reduces the computational cost of finding the vorticity at a point in a vorticity field.

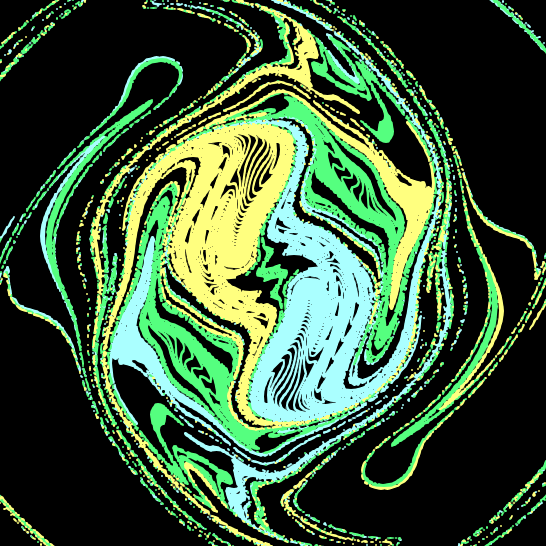

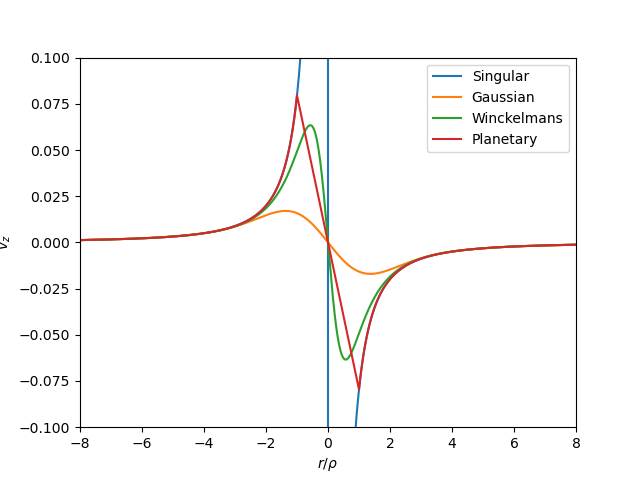

Next, we want to see how velocity induced by a regularised particle compares to that of singular particle. Plotting the induced velocity with respect to radius (this time the praticle has \(\alpha = \{0, 1, 0\}\):

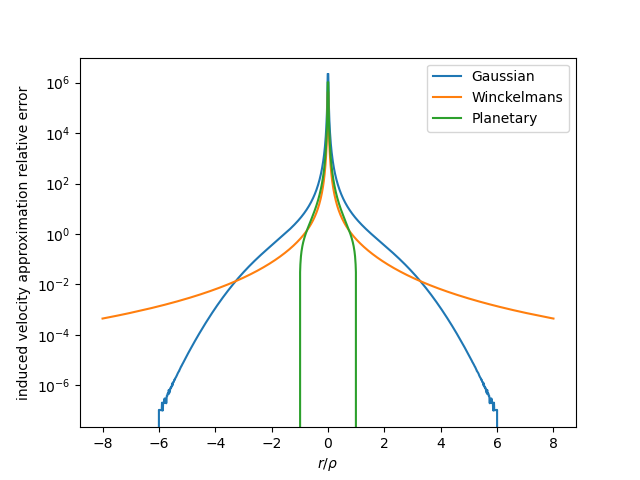

Near the centre of the particle, the induced velocities are very different. In the farfield, they converge. If instead we plot the error resulting from approximating the regularised particle with a singular particle, we get:

Evidently an advantage of planetary regularisation is that we can approximate the induced velocity with the singular one as soon we’re beyond the \(r/\rho=1\). The error for the Gaussian regularisation falls very rapidly too. Winckelmans regularisation, not so great in this respect. If we can approximate our regularised particles with a singular one, we might be able to apply tree codes / fast multipole methods developed for singular particles to regularised problems so long as we set a minimum radius from the particle (good separation is needed anyway for the multipole expansions to work properly).

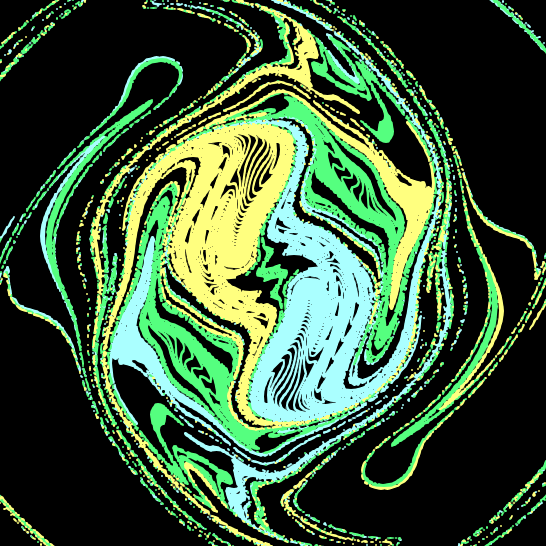

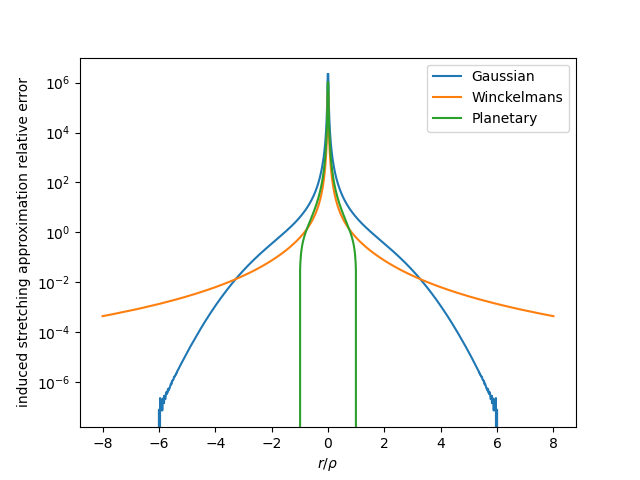

Vortex stretching terms are next. This is related to the gradient of the velocity field, so I expect a similar conclusion as that obtained for velocity. But it doesn’t hurt to check by plotting it.

Heartwarmingly, we get the same result (except for a small amount of numerical noise due to using single precision for computation).

The take away here is that we don’t have to get far from regularised particles before we can pretend that we’re working with singular particles instead, possibly leading to either big computational savings or the reuse of carefully writting code.

This distance depends on the choice of regularisation, but Gaussian regularisation is pretty good from this perspective.