Quadratures with weak singularities

A problem

We have a singular definite integral which is complicated enough that tables don’t give us a solution immediately. What do we do?

Lets say it looks a little like this:

\[\int_a^b f(x) dx\]where \(f(x)\) is singular at \(x_s\).

Integration by parts

For problems posed analytically, integration by parts often produces a solution. We might have a problem where \(f(x) = g(x) h(x)\), where \(g(x)\) is non-singular, and \(h(x)\) is singular. Using integration by parts we can make \(h(x)\) non-singular.

For example,

\[\int_0^\pi \frac{\cos(x)}{\sqrt{x}} dx\]where we can say \(g(x) = \cos(x)\) and \(h(x) = 1/\sqrt{x}\), being singular as is at \(x=0\). Using integration by parts,

\[\int_a^b g(x) h(x) dx = \left[g(x) \left[\int h(x) dx\right] \right]^b_a - \int^b_a \left[\int h(\xi) d\xi \right] \frac{d g}{dx}(x) dx\] \[\int_0^\pi \cos(x) \frac{1}{\sqrt{x}} dx = \left[ \cos(x) \cdot 2\sqrt{x} \right ]^\pi_0 - \int^\pi_0 2\sqrt{x} \cdot -\sin(x) dx\] \[\int_0^\pi \cos(x) \frac{1}{\sqrt{x}} dx = -2\sqrt{\pi} + \int^{\pi}_0 2\sqrt{x}\sin(x) dx.\]The non-singular integral on the right hand side can be evaluated numerically, since it is no longer singular. Alternatively, a closed form solution - albeit a somewhat unpleasant one - can be obtained with a CAS.

Singularity subtraction

In practice, I can’t think of an occasion where the integration by parts method has been useful. For numerical methods, the numerical part is often the non-singular part. Whilst it is possible to take derivatives, either numerically or by taking derivatives of whatever approximation is in use, it is often easier to take a different, and rather common approach to removing the singularity: singularity subtraction.

The integral is rewritten as:

\[\int_a^b h(x) (g(x) - g(x_s)) dx + g(x_s) \int_a^b h(x) dx\]where \(h(x)\) is often analytic. Reusing the earlier example,

\[\int_0^\pi \cos(x) \frac{1}{\sqrt{x}} dx = \int^\pi_0 \frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}(\cos(x) - \cos(0))dx + \cos(0) \int^\pi_0 \frac{1}{\sqrt{x}} dx\] \[\int_0^\pi \cos(x) \frac{1}{\sqrt{x}} dx = \int^\pi_0 \frac{\cos(x) - 1}{\sqrt{x}}dx + 2\sqrt{\pi}\]If \(g(x)\) (the non-singular part) is numerical, singularity subtraction is also very easy to apply. Care must be take to ensure that quadrature points don’t line on the singularity(s).

Coordinate transforms

Now to the bit that isn’t such common knowledge - remapping quadratures. In effect, we’re changing the variable of integration:

\[\int_a^b f(x) dx = \int^{x=b}_{x=a} f(x(\eta)) \frac{dx}{d\eta} d\eta\]where \(x(\eta)\) is chosen such that the derivative is zero at the singularity, \(\frac{dx(\eta_s)}{d\eta}=0\). Generally, \(x(\eta)\) is also chosen such that \(x(a)=a\), \(x(b)=b\) and \(a \geq x \geq b\). This transform is then applied to a qaudrature, such that a numerical integrand becomes integrable. Additionally, normally a transform is applied such that \(a=-1\), and \(b=1\) (for integrals in a finite interval at least - infinite limits are possible, but won’t be considered here).

J.F.C. Telles provides low order polynomial transforms. Telles’ second order transform is subject to the condition that the singularity is weak (ie. integrable even when \(a=x_s\) or \(b=x_s\)), and is singular at one of the limits of integration.

The transform is as follows (remembering that \(a=-1\) and \(b=1\), \(\eta_s=x_s\) and \(\lvert x_s \rvert = 1\)):

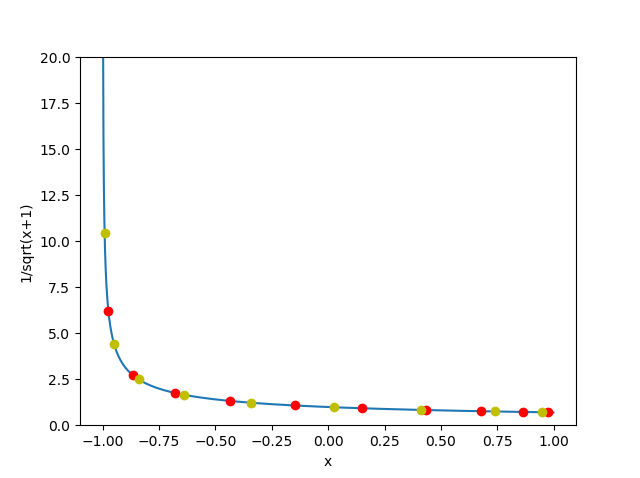

\[x(\eta) = \frac{(1-\eta^2)\eta_s}{2} + \eta\] \[\frac{dx}{d\eta} = 1-\eta\eta_s\]The following plot demonstrate the remap for \(f(x) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}\). The plot shows the \(f(x)\) with the red dots indicating a Gauss-Legendre quadrature. The yellow points indicate the quadrature after remapping.

Notice how the remapped yellow points are bunched towards the singular bit. The transformed integrand is a little special here - the remapped solution is a constant.

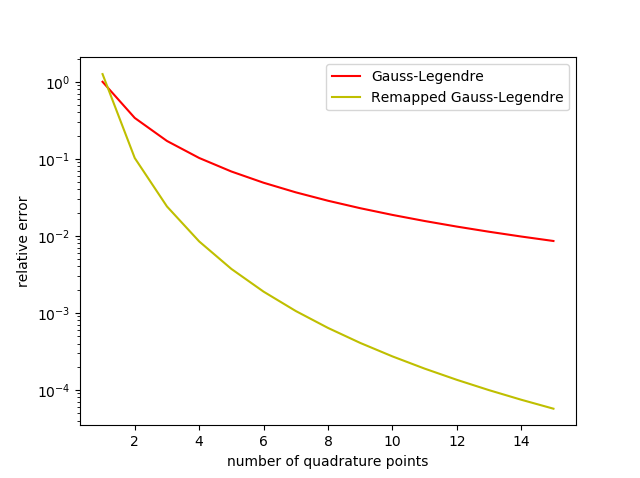

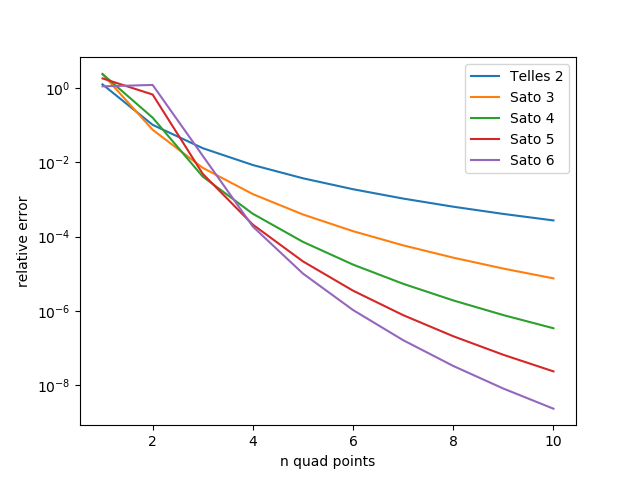

\[\frac{1}{\sqrt{x(\eta) + 1}} \frac{dx}{d\eta} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{\frac{-(1-\eta^2}{2} + \eta + 1}}(1 + \eta) = \sqrt{2}\]We can plot the error of \(n\)-point quadratures and see how useful remapping is. If we examine the logarithmic singularity \(f(x) = \log(x+1)\) and modify a Gauss-Legendre using the Telles quadratic scheme we obtain:

The remapped quadrature does much better than the vanilla quadrature.

But wait, there’s more.

Why stop at quadratic? We can use higher order polynomial transforms. A general polynomial remap for intervals with a singularity at one end is that of Sato.

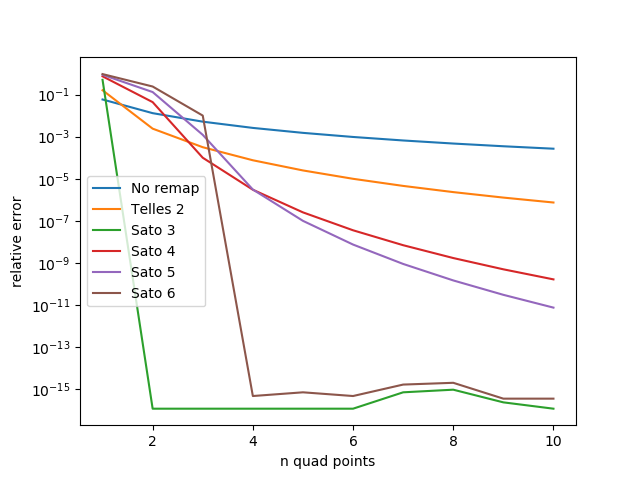

\[x(\eta) = \eta_s - \frac{\eta_s}{2^{k-1}}(1 - \eta_s \eta)^k\] \[\frac{dx}{d\eta} = k 2^{1-k} \eta_s (1 - \eta_s \eta)^{k-1}\]where \(k\) is the order of the remap, and as with above \(x_s = \eta_s\) and \(\lvert \eta_s \rvert = 1\). We can look at the effect on the accuracy of a remapped Gauss-Legendre remap for \(f(x) = \log(x+1)\) again.

Increasing the order of the transform improves the result of the quadrature. However, there is a limit the order of transform that can practically be used. Remember how the points all bunch around the singularity? With higher and higher order transforms the accuracy of double precision variables eventually becomes a problem. Generally, one does well to avoid higher than fifth order transforms.

Lets try some other integrands, just to convince ourselves that the two used so far ain’t special.

\[f(x) = (x+1)^{-1/3}\]

The third and sixth order transforms do especially well for the same reason Telles 2 worked well on \(1/\sqrt{x}\).

Also

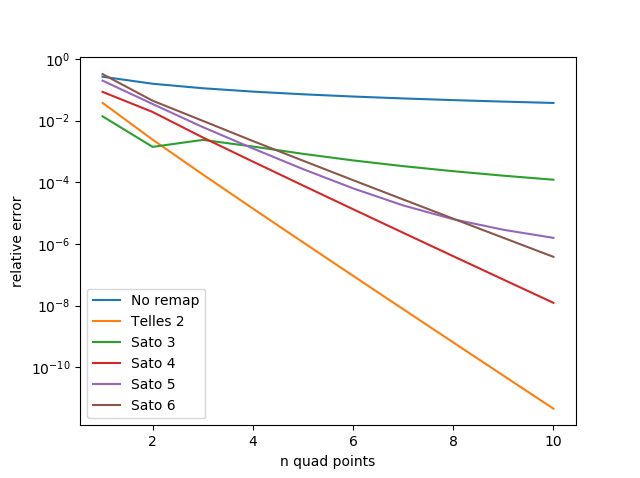

\[f(x) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - \left(\frac{x}{2} - \frac{1}{2}\right)^2}}\]

Here the even order polynomial transforms do best, with Telles 2 doing best of all, bucking the trend of higher order being better.

What other remaps and options are there?

Unsurprisingly, there are no lack of transforms available. I haven’t touched on the topic here of non-weak singularities, and singularities within the limits of integration (without splitting integral in two). Both of these can be handled numerically. Nor have I touched on non-finite limits of integration. Transforms of interest include:

- Telles’ cubic transform, suitable for weakly singular integrals where the singularity is within the limits of integration.

- Sigmoidal transforms - transforms based on trig functions.

- Tanh-sinh transforms - that effectively spread an singularity over an infinite interval (as I understand it).

- Doblare & Garcia’s transform, which allows quadrature to be applied to a singular or hypersingular integrand, by observing the importance of symmetry about the singularity of the quadrature (so I think).

Perhaps it is also worth noting that it may be better to start by using an appropriate quadrature in the first place. Here I’ve focussed on mis-applying Gauss-Legendre quadrature to singular problems. Gauss-Jacobi quadrature are more suitable, if more difficult to generate. Fortunately, if you embrace the modern practice of using mystery code automatically downloaded from the internet, other people will help you with this - for example, see FastGaussQuadrature.jl.

Recommended reading:

-

J.C.F. Telles A self-adaptive co-ordinate transformation for efficient numerical evaluation of general boundary element integrals, International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering, 1987.

-

K.M. Singh and M. Tanaka On non-linear transformations for accurate numerical evaluation of weakly singular boundary integrals, International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering, 2001.