Vortex particles and regularisation distances

A vorticity \(\mathbf{\omega}(\mathbf{x}, t)\) can be approximated by a group of vortex particles such that

\[\mathbf{\widetilde{\omega}}(\mathbf{x}, t) = \sum_{i} \frac{\mathbf{\alpha}_i(t)}{\sigma^3} \zeta\left(\frac{\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x}_i(t)}{\sigma}\right)\]where \(\mathbf{\widetilde{\omega}}(\mathbf{x}, t)\) is the regularised vortex particle approximation of the field (and hence is not divergence free), \(\mathbf{\alpha}_i\) is the vorticity of the vortex particles, and \(\zeta(\rho)\) is the regularisation function. The regularisation uses a regularisation scale (often referred to as the particle radius) \(\sigma\) for normalisation.

It is commonly accepted that vortex particles must “overlap” in order for the method to be convergent. This is required to minimise the divergence of \(\mathbf{\widetilde{\omega}}(\mathbf{x}, t)\). If one considers vortex particles as small segments of filament, these small bits of filament overlap to make the filament continuous. Otherwise Helmholtz’s law is broken.

Do we have to abide by this rule to get results? No. Singular vortex particle often produce perfectly good results. There are also plenty of visualisations where the vortex particles don’t appear to overlap.

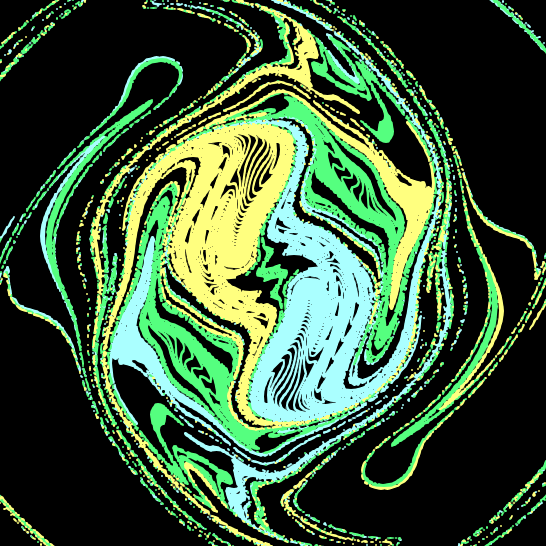

So, for all I know this post is about aesthetics. I’m not an expert on vortex particle methods. But, like so many people, I do like a good lookin’ visualisation. So lets look at a vortex particle tube problem that I use to test my vortex particle code, CVortex.

The vortex particles only have vorticity in the tangential direction and use a gaussian regularisation. There is only a single layer of particles. As the problem becomes more refined, the walls of the tube become more singular. It converges (or rather, given infinite particles, ought to converge) to a case where flow only flows through the ends of the tube, never the walls.

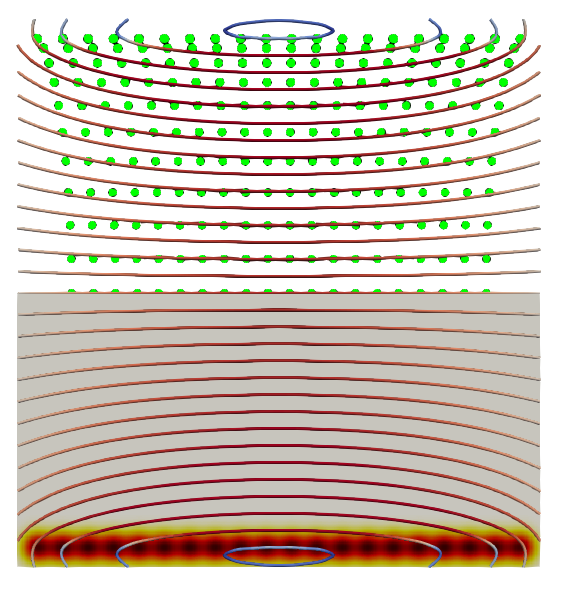

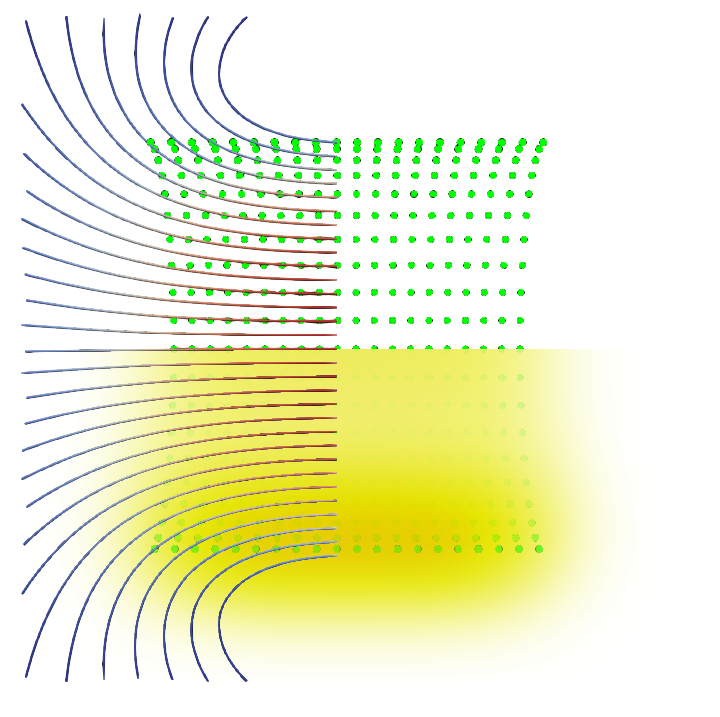

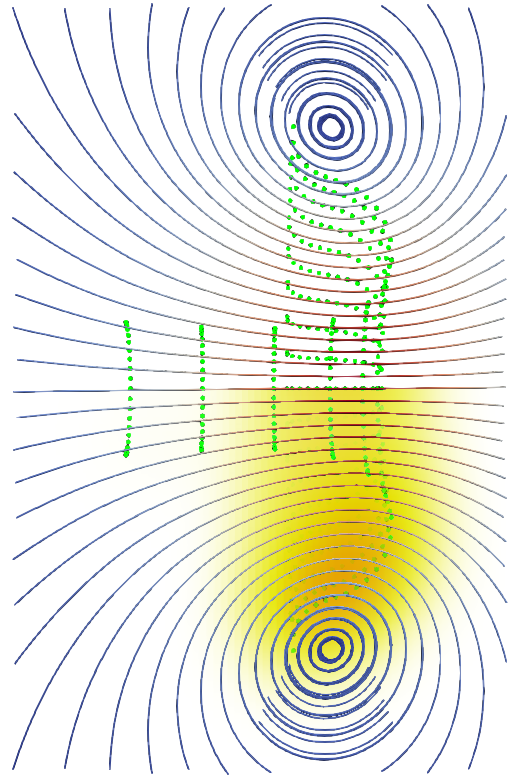

We’ll start with a regularisation distance twice the distance between particles:

The vorticity field appears very blurry, but continuous. The vorticity density is stronger near the core of the the vortex particle layer. The streamlines have a habit of going through the wall of the tunnel. This is perhaps because they must be more than two regularisation distances (probably) away from the wall to actually be within the tube of vorticity.

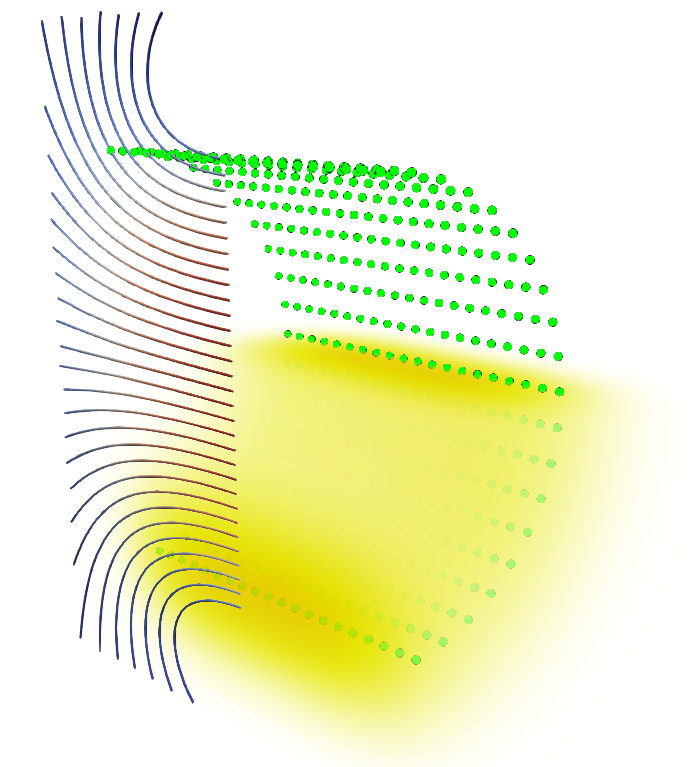

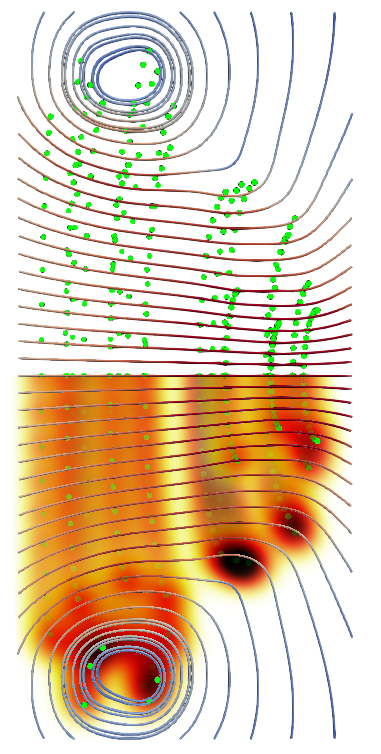

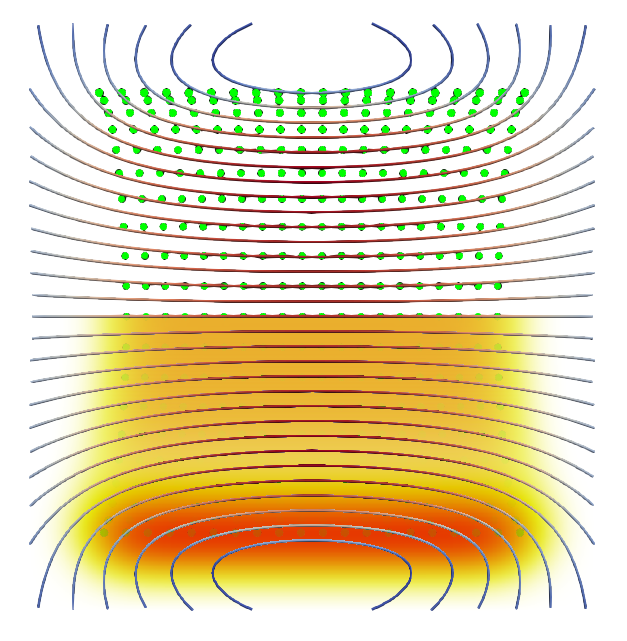

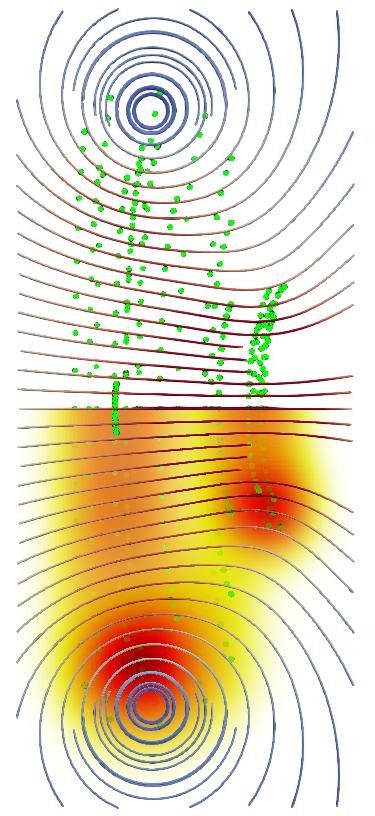

We can half the regularisation distance the the distance between the particles. Keeping the same colour bar:

Unsurprisingly, the vorticity is now confined to a smaller volume, reaching higher peak densities. The streamlines curve more sharply around the ends of the tunnel.

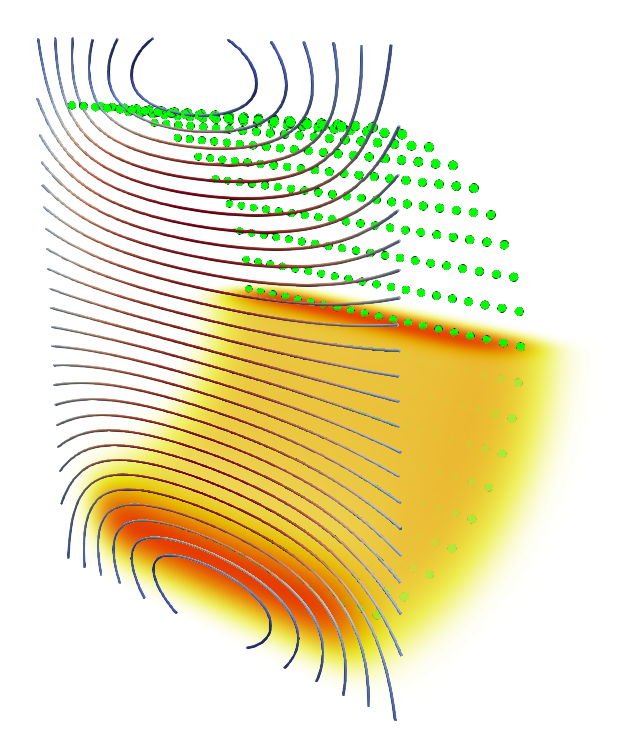

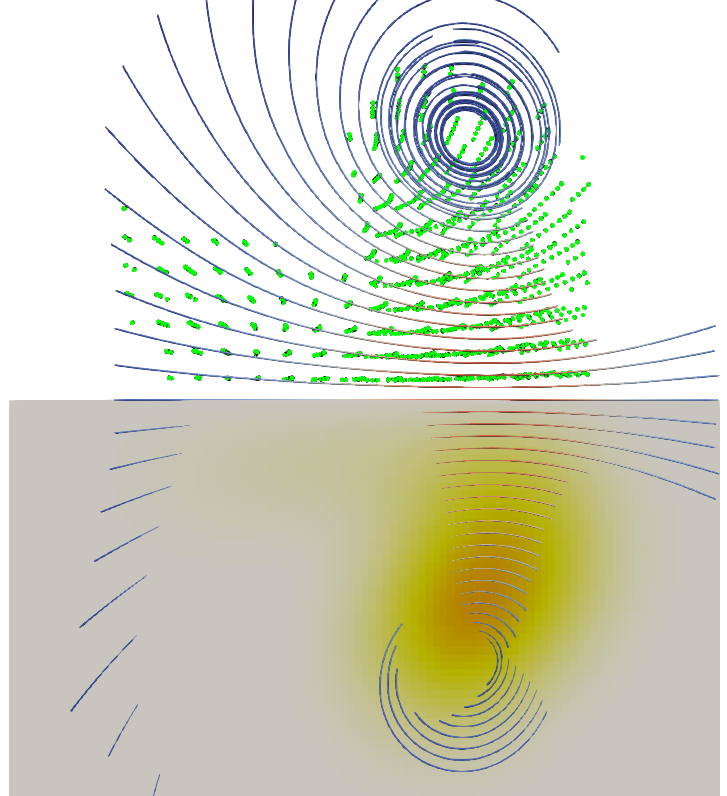

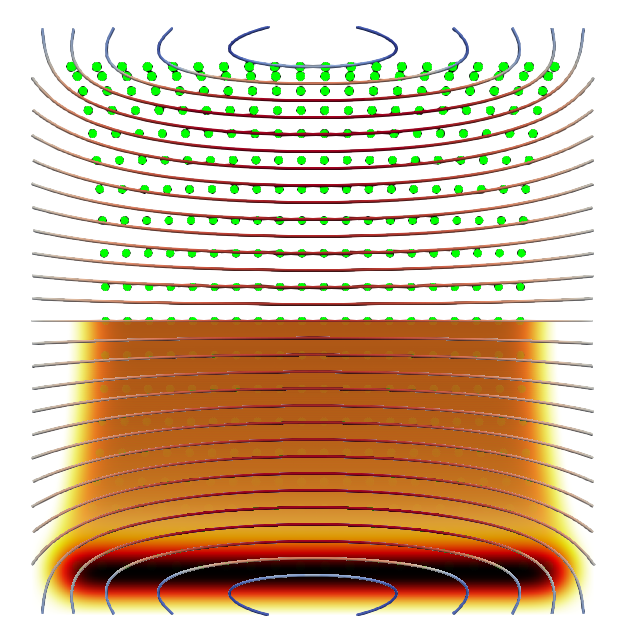

We can decrease the regularisation distance further, still keeping the same colour bar (although saturating our scale).

The trends continue with the regularisation distance at half the inter-particle spacing.

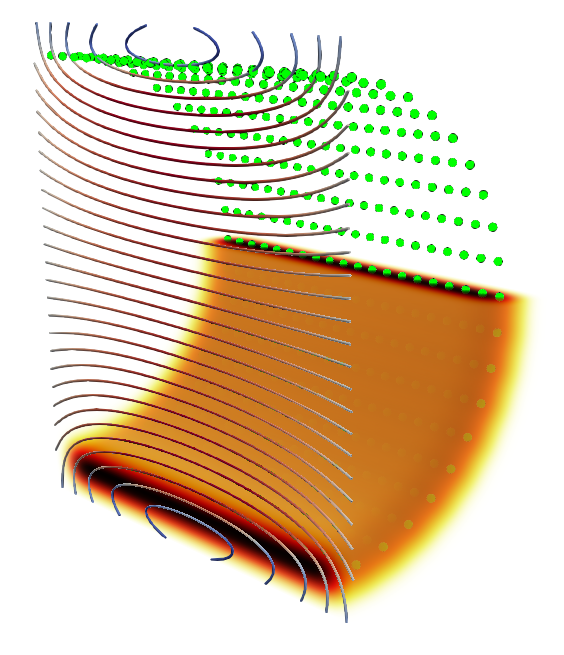

Again, dividing the the regularisation distance in half again to a quarter of the particle spacing, we now get something more problematic looking.

Note that here the colour bar has been adjusted such that it range is four times the previous scale. The structured mesh is now so fine that my PC doesn’t have enough RAM to manage volume rendering. Individual particles are now visible. Since the zone of vorticity no longer join up, this arrangement isn’t divergence free.

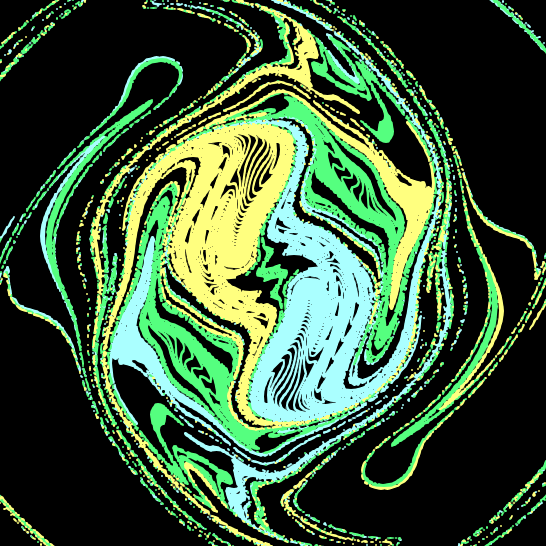

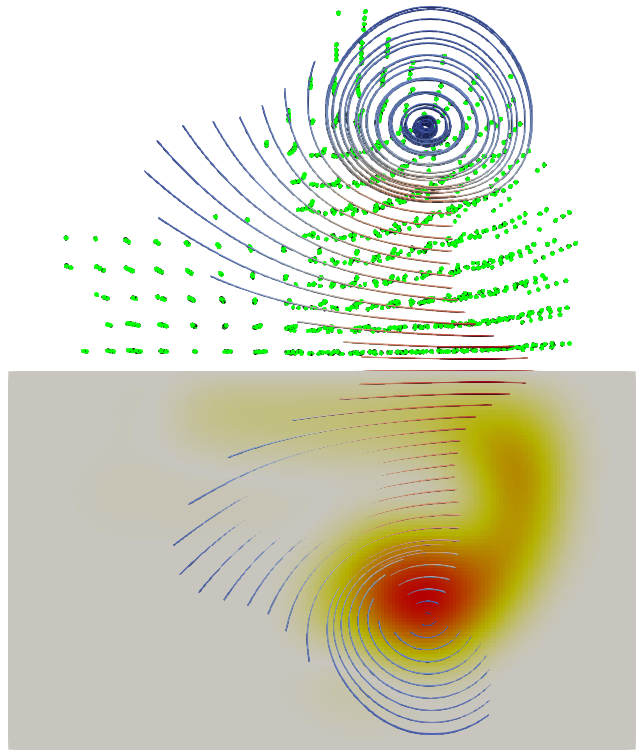

Now, we can look at what happens as the vortex tunnel develops.

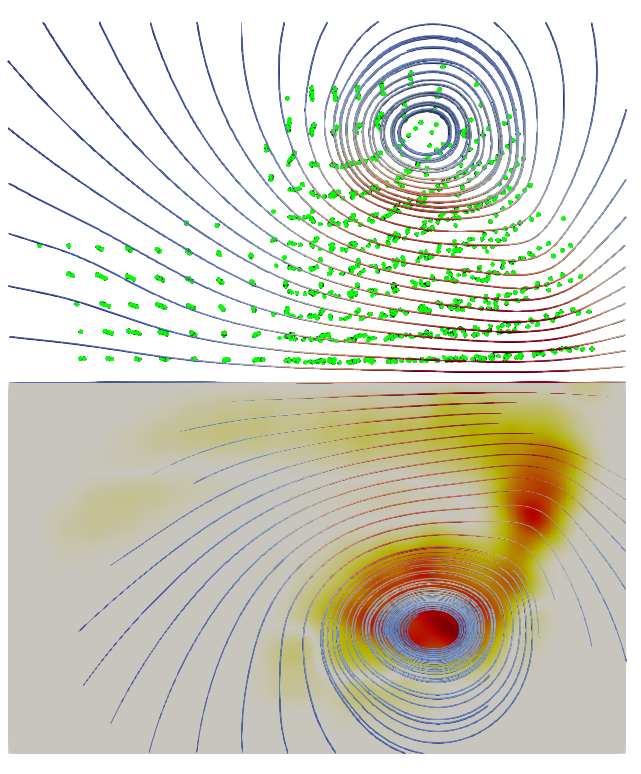

Side by side we have the results for regularisation distances of 2, 1 and 0.5 particle separations respectively. Images sizes aren’t directly comparable.

The result has considerable variation. The result for the smallest regularisation shows separate vortex rings, a far cry from the continuous shear layer our tube initially was supposed to represent. The remaining two results possibly show a continuous shear layer. Its hard to say. But the finer regularisation distance produces two main areas of high vorticity, compared to the single ring that seems to have formed in the leftmost case.

Whilst it would be hoped that the different cases would produce similar results, they do not. Part of the reason for this is the spreading out of vortex particles during the simulation.

In a past post I showed how vortex particle redistribution could be used to obtain better results in 2D. Here we use the \(M_4'\) redistribution kernelin 3D every 10 time steps to stop our particles spreading out too much. Increasing the step would allow the to spread out more, and possibly reduce computational cost, but would increase divergence in the result. Reducing the number of steps between each redistribution would cause the results to be less Lagrangian (as in, grid-free).

Firstly, we look at what happens with the simulation at regularisation distances of 1 and 2 of the original spacing respectively.

For the 2 spacing one (right), the result is practically identical to the non-redistributed result. Apparently in the non-redistributed case, the particles didn’t spread out enough to be a problem.

The single spacing result differs. A clearly identifiable main vortex and shear layer are visible.

If we look at the result for using a regularisation distance of 0.5 the particle spacing, the results are not so pretty:

Like in the single space regularisation, a main vortex and shear layer can be identified. But they are messy and unnatural looking. Rings of vorticity appear to have escaped the main system.

What can we learn from all this? From the initial setup it appears that using a regularisation distance of 0.5 times the particle spacing was sufficient. But by the time the system had developed, this gave bad results, redistribution or no redistribution.

Its tempting to say that a regularisation distance of 1 particle separation is sufficient, or that 2 is excessive and wasteful (for it implies that we used more particles than needed). But to read too much into the results obtained is a mistake - by changing the the regularisation distance without changing the number of particles, the problem we a looking at is changed.